-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 25

AST Guide

This page currently under construction.

The Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) is the primary data structure to operate on in Overture development. Most things you do in Overture involve the AST. This guide provides a tour of the AST, its structure and relevant details. It also relates the tree to the VDM language. Speaking of which, working knowledge of VDM is assumed. For more about VDM, visit the main Overture page.

Any given AST object is a tree structure (duh). It consists of one or more root nodes at the top and various child nodes below them. Nodes have various fields to hold information. Most notably, child nodes are fields of their parent nodes and that's how the tree is structured.

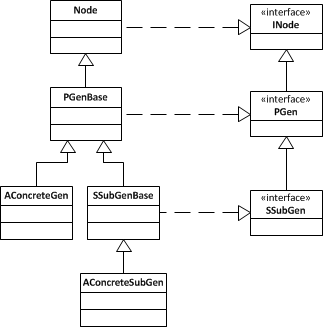

As for the various classes that provide the implementation of the AST, they all fall somewhere along the AST class hierarchy. This hierarchy is composed primarily of interfaces and abstract classes defining the kinds of nodes in an AST and their connections. At the bottom of the hierarchy, there are several concrete classes that correspond to the various versions of each node. The figure below shows the AST hierarchy for a generic set of nodes.

At the top of hierarchy is the INode interface . This defines the common

behaviour of all nodes. The Node class is an abstract class providing default

implementations of all methods defined in INode. As we move down the tree,

it's the same thing: PGen is an interface defining the behaviour of all nodes

in the Gen family and PGenBase is an abstract class providing a default

implementation of the behaviour. The same is true for SSubGen, which defines

and provides default implementation for the behaviour of the sub-family.* At

both P and S levels, we can have concrete classes that provide implementations

of specific nodes. However, there are no concrete nodes the top. Every concrete

node must inherit from a P or S base class. Also, there can be multiple of

levels of S families but there is only P level.

* For those wondering P stands for production and S stands for sub-production, as in the grammar for the VDM language.

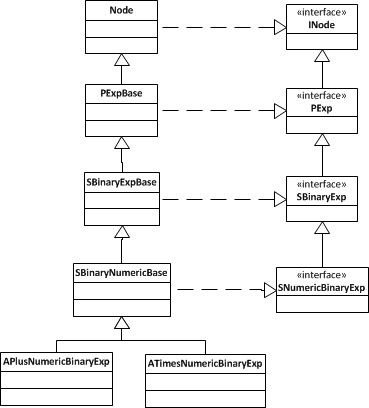

In case the above was a bit confusing, here is a more specific example showing a small excerpt of the tree, showing plus and times arithmetic expressions.

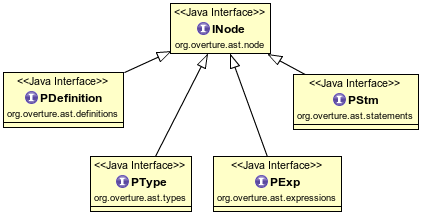

Broadly speaking the P families correspond to the various syntatical elements

of VDM. For example PDefinition corresponds to VDM definitions, PExp

corresponds to expressions and PBind corresponds to bindings. It's not worth

it to cover all the P families (there are 30 them) but here are some

of the more important ones:

-

PDefinition: represents definitions, including classes, modules, operations, etc.. Generally speaking, whenever you havename == definition, you will have a corresponding pdef. As you'd expect this is a very large family: including sub-family interfaces, there are 44 subclasses ofPDefinition. -

PStm: represents statements. Statements are present in the bodies of operations. Special attention is drawn to the block statement which allows you to compose multiple statements together. -

PExp: represents expressions, such numeric, quantified and set expressions. Expressions are are always present in the bodies of functions, in pre- and post-conditions and in invariants. They also occur in certain statements (e.g. the condition of an if-then-else statement is an expression). -

PType: an exception as it does not represent a syntactic element (VDM types definition arePDefinitionnodes).PTypenodes represent the type hierarchy of VDM and are used to encode type information directly in the AST.

We have already discussed PType nodes as an example of an AST node that does

not represent a syntactic element. There is another node family that does not

strictly correspond to syntax: the Lex Tokens. In fact, the tokens are not part

of the tree in the traditional sense (they are not part of the tree

specification file). Nonetheless, they are subclasses of Node and they're

part of any tree produced by the parser. This family, defined by the IToken

interface and the Token abstract class, represents the various lexical tokens

produced by the lexer and fed to the parser. These nodes are always attributes

of other nodes in the tree. Their mains use is when pretty-printing the tree

except for the LexNameToken which is used to identify names in the tree (for

lookups, disambiguations, etc.). Unless you are doing fairly sophisticated tree

transformations, you shouldn't need to worry too much about them. The only one

you will use with any regularity is LexNameToken

This section notes some unintuitive behaviour of the AST. It's particularly relevant for anyone doing tree transformations. The main issue is one of node parenthood.Every field has a parent node (the node of which is is a field). But things get a little more complicated since there are two kinds of fields: Graph and Tree.

- Graph fields have a pretty standard behaviour. A single object can be set as a graph field of multiple nodes (Graph fields are just references). However, if you ask a Graph node for its parent, you will only get the first one (in other words, the first time you set the node as a field somewhere, it's parent reference will be set. The next time the node is set as a field, since a parent already exists it will not be set). Because a graph field is just a reference, you can make changes the parent and nothing will happen to the child (this includes removing the child or setting a new one).

-

Tree fields on the other hand can only have a single parent and are

effectively tethered to it. This means that if you change the child, the new

one will have the parent updated and the old one will lose the parent

reference. To put it another way, the parent of a Tree field must always

be the node on which is is set. The AST has side-effect code spread through

it to preserve this property so if you change a Tree node of a node,

the old child will have its parent set to

nulland the new child will have its parent overridden. - Whether a node is a Tree or Graph depends entirely on the field type of its parent. From the child node's perspective there is no difference to being a Tree or Graph (in fact, there is no way to tell).

Confused yet? Maybe a little. It gets even worse since the getters and setters for fields say nothing about whether a field is Graph or Tree neither in their names nor their Javadoc. The only way to tell is to inspect the method bodies (Tree setters have a lot more side-effects) or inspect the class variables. This is made slightly more complicated by the fact that for a given concrete node, its various fields and methods are scattered across its inheritance hierarchy.

In practical terms, this issue comes up a lot when you do tree transformations

or manual tree constructions. As you move nodes around the tree (in effect

establishing new parent/child relations and destroying old ones) you may

accidentally end up in a situation where a node's parent is null. If that

parent is required for something else, the tool will crash. It's not often

immediately obvious whether or not the parent will be needed -- it depends on

the use of the future tree.

This is even more problematic if your new tree somehow changes the old one. With the exception of the Type-Checker, components are not allowed to change the AST of a model (otherwise you would not be able to run multiple analysis on the same tree).

So what the solution? Cloning! If you clone a node before setting it as a child, the cloned node will be different and so the parent/child relation of the original node will be preserved. This is a good rule of thumb when doing transformations or creations. If you to place an existing tree node somewhere else, clone it first. A few caveats though:

-

Cloning everything increases the number of references in the tree and will lead to performance decreases (though, nothing notable). If you are certain it's safe, avoid cloning. However, when in doubt it's better to be safe that sorry.

-

Node cloning is shallow. While it's sufficient to get past the parent/child issues, it does not protect from other changes. If you need a completely new node that is the same as the old one, you have to instantiate a new one manually and set the relevant fields.

-

List fields (fields consisting of lists of nodes) cannot be cloned directly. You need to create a new list, iterate over the old one and clone and add each node individually.

-

In case it wasn't obvious, it bears repeating: none of these issues affect Graph fields so don't bother cloning them.

-

Distinguish between children and graphs

-

Importance of preserving the AST (clone a lot!)

-

weird side-effects when setting new nodes

As you might have guessed by now, the AST is not handwritten or maintained.

It's generated by a tool called

AstCreator (also maintained by

us). You can look in src/main/resources/overtureII.astv2 of the ast module

to see the specification file for the AST used in Overture.

The syntax for the AST specification is actually simple, in case you need to change or create a new one. However, note that changes to the main AST are not merged in without prior discussion among the developers. In general, we want the AST to be stable.

The AST specification file consists of 4 sections:

Packages

...

Tokens

...

Abstract Syntax Tree

...

Aspect Declaration

...

-

The

Packagessection defines the top level package names for the AST. There are two packages to define:basefor the nodes themselves andanalysisfor the visitors. In both cases, sub-packages will be generated (for node families, interfaces, etc.). -

The

Tokenssection defines tokens or external classes that can be used as fields in the AST. All of these classes must be clonable. All token definitions consist of a token name and a'-delimited string defining the token. Multiple types of tokens can be specified:- basic tokens (instances of the Token class). They are generated from

their name and the symbol they represent. Ex:

plus='+';. - standard Java. These use the Java basic types in class form. They are

defined by using

java:as a prefix. Ex:java_Integer='java:java.lang.Integer'; - enum tokens. These are similar to Java tokens but they use a Java enum.

They are defined using

java:enum:as prefix. Ex:scope = 'java:enum:org.overturetool.example.Scope'; - external classes. These use any external Java class that must implement the

ExternalNodeinterface. They are defined by usingjava:as prefix. The Overture AST makes extensive use of this kind of token. Ex:location='java:org.overture.ast.lex'; - external nodes. These are also external Java classes but they must

implement the full

INodeinterface. They're essentially a way for allowing nodes created outside AstCreator to still be a part of the tree. They are defined by using thejava:node:prefix. Ex:LexNameToken = 'java:node:org.overture.ast.intf.lex.ILexNameToken';

- basic tokens (instances of the Token class). They are generated from

their name and the symbol they represent. Ex:

-

The

Abstract Syntax Treesection describes the tree itself. Its syntax is fairly straightforward. Coming Soon... -

The

Aspect Declarationallows you to add fields to the base classes (and their subclasses). This is simply a convenience feature to add recurring fields to the same place. The syntax is%<node name> = [<field name>]:<field type>. The node name can be either the root node or one of the sub-familes (ex:%exp.#unary).