WorldDynamics.jl

This is the documentation page for WorldDynamics.jl, an open-source framework written in Julia for world dynamics modeling and simulation.

The World Dynamics Project

The World Dynamics project aims to provide a modern framework to investigate models of global dynamics focused on sustainable development based on current software engineering and scientific machine learning techniques. Our group is developing a Julia library to allow scientists to easily use and adapt different world models, from Forrester's World2 to Meadows et al.'s World3 to recent proposals. By enabling an open, interdisciplinary, and consistent comparative approach to scientific model development, our goal is to supply high-quality information to global policy making on environmental and economic issues.

Getting started

From the Julia REPL, install the package with

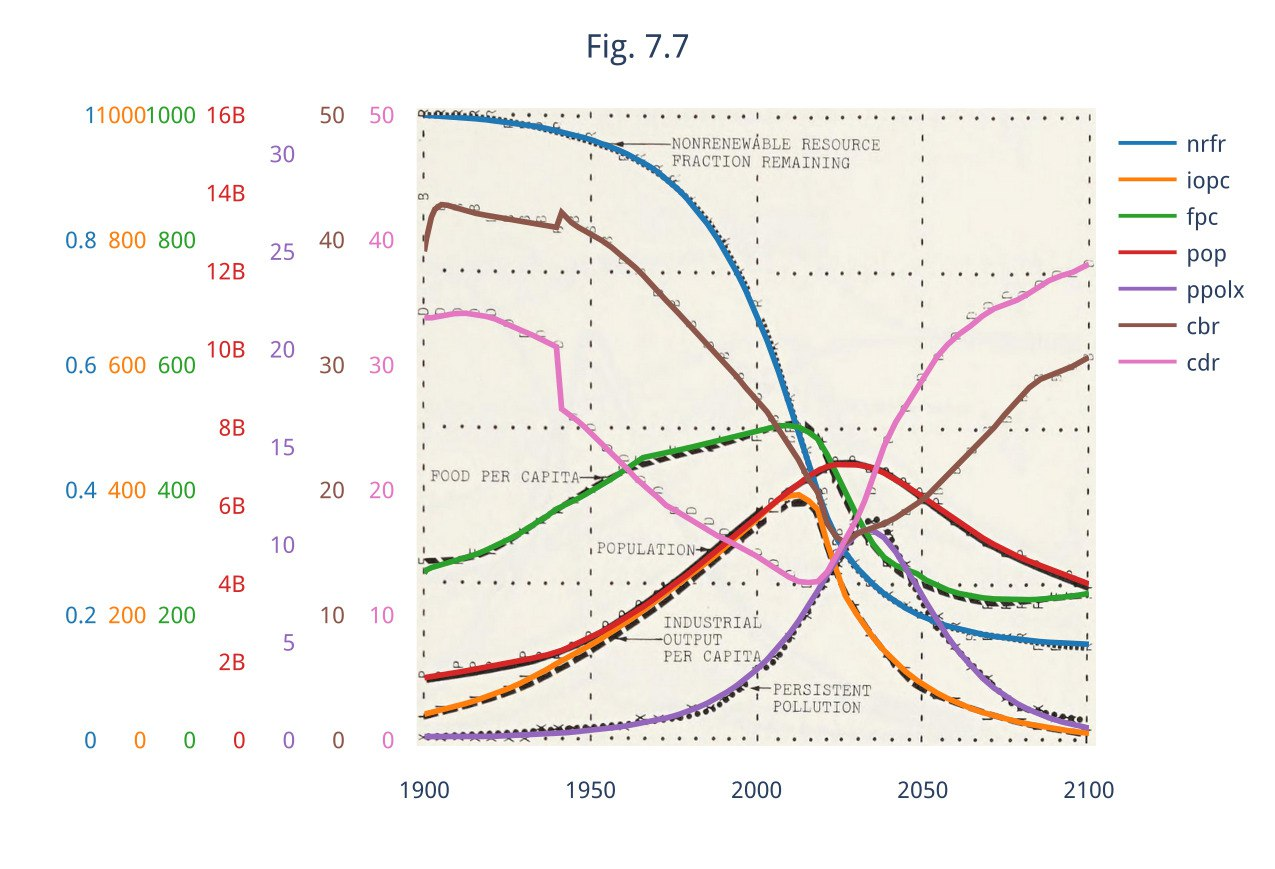

]add WorldDynamicsYou can now use the package, e.g. for reproducing Figure 7.7 from the book Dynamics of growth in a finite world:

using WorldDynamics

-World3.fig_7()Here is the output superposed to the original picture:

The docstrings of each figure function contain specific pointers to the corresponding original figure numbers and captions.