JavaScript unlike other programming languages, it’s single threaded. That means, code execution will be done one at a time. So there is just one thing happening at a time. When you open a website in the browser, it uses a single JavaScript execution thread. That thread is responsible to handle everything, like scrolling the web page, printing something on the web page, listen to DOM events (like when the user clicks a button), and doing other things. Since code execution is done sequentially, any code that takes longer time to execute, will block anything that needs to be executed. Hence sometimes you see below screen while using Google Chrome. Same on Node.js as JavaScript code runs on a single thread too.

You just need to pay attention to how you write your code and avoid anything that could block the thread, like synchronous network calls or infinite loops. E.g.

while(true){}Any code after above statement won’t be executed as while loop will loop infinitely until system is out of resources. This can also happen in infinitely recursive function call. Thanks to modern browsers, as not all open browser tabs rely on single JavaScript thread. Instead, they use separate JavaScript thread per tab or per domain

First let's clarify some things:

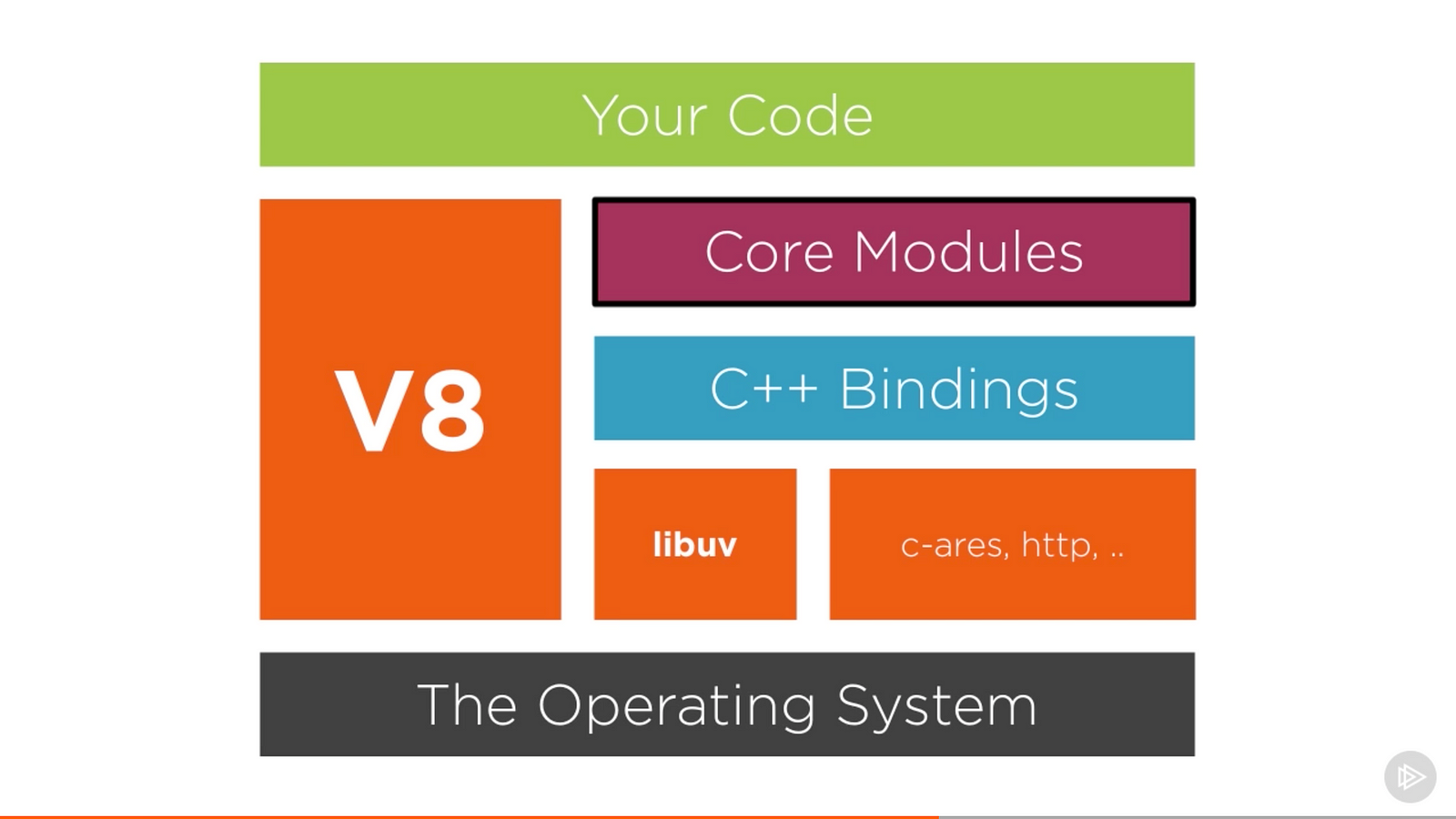

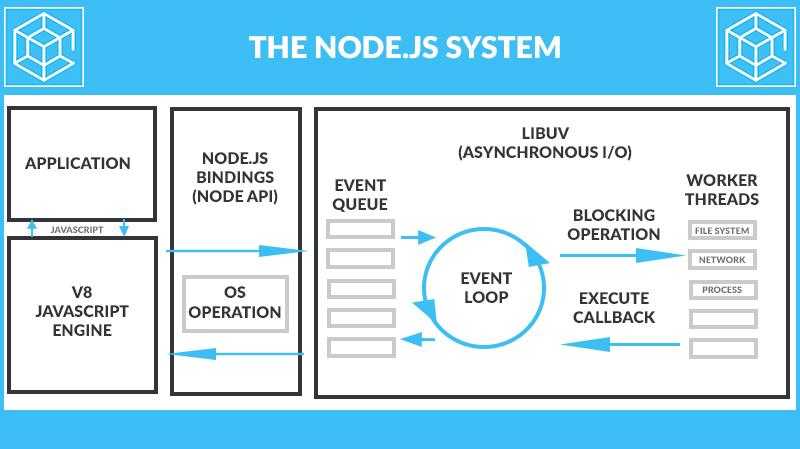

a) NodeJS is JavaScript runtime built on Chrome V8 JavaScript engine, but you can pick another engine too.

b) Javascript is single-threaded and so is any Javascript implementation like NodeJS.

c) V8 provides default implementation of the Event Loop. NodeJS is using event-loop provided by the libuv

NodeJS System:

Javascript Runtime Engine:

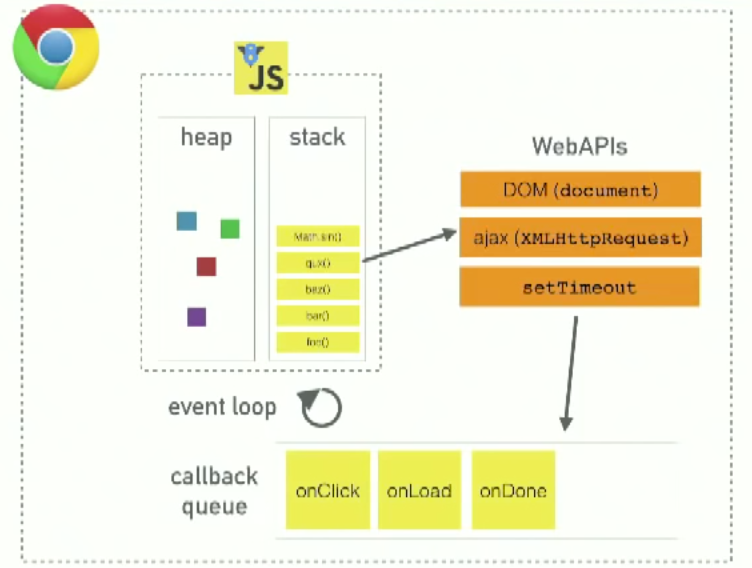

Like any other programming language, JavaScript runtime has one stack and one heap storage.

-

Heap - A heap is a free memory storage unit where you can store memory in random order. Objects are allocated in a heap which is just a name to denote a large mostly unstructured region of memory. Heap is managed by the JavaScript runtime and cleaned up by the garbage collector.

-

Stack - This represents the single thread provided for JavaScript code execution. Function calls form a stack of frames. Stack is LIFO (last in, first out) data storage which store current function execution context of a program.

-

Browser or Web APIs are built into your web browser, and are able to expose data from the browser and surrounding computer environment and do useful complex things with it. They are not part of the JavaScript language itself, rather they are built on top of the core JavaScript language, providing you with extra superpowers to use in your JavaScript code. If you’re a Node.js developer, these are the C++ APIs.

In general, in most browsers there is an event loop for every browser tab, to make every process isolated and avoid a web page with infinite loops or heavy processing to block your entire browser.

The environment manages multiple concurrent event loops, to handle API calls for example. Web Workers run in their own event loop as well.

You mainly need to be concerned that your code will run on a single event loop, and write code with this thing in mind to avoid blocking it.

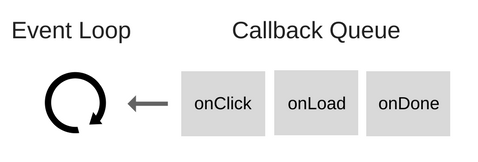

The call stack is a LIFO queue (Last In, First Out). The event loop continuously checks the call stack to see if there’s any function that needs to run. So it's job is to look at callback queue and once there is something pending in callback queue, push that callback to the stack. The event loop pushes one callback function at a time, to the stack, once the stack is empty. To visualize, how JavaScript executes a program, we need to understand JavaScript runtime.

Hence, first stack entry is foo(). Since foo function calls bar function, second stack entry is bar(). Since bar function calls baz function, third stack entry is baz(). And finally, baz function calls console.log, fourth stack entry is console.log('Hello from baz'). Until a function returns something (while function is executing), it won’t be popped out from the stack. Stack will pop entries one by one as soon as that entry (function) returns some value, and it will continue pending function executions.

Let’s pick another one example:

const bar = () => console.log('bar')

const baz = () => console.log('baz')

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo')

bar()

baz()

}

foo()This code prints:

foo

bar

bazAt this point the call stack looks like this:

The event loop on every iteration looks if there’s something in the call stack, and executes it until the call stack is empty:

So what is the event loop after all?

Browser comes with a JavaScript engine which provides JavaScript runtime environment. For example, Google chrome uses V8 JavaScript engine, developed by them. But guess what, browser uses more than just a JavaScript engine. This is what browser under the hood looks like.

JavaScript runtime actually consist of 2 more components viz. event loop and callback queue. Callback queue is also called as message queue or task queue.

The Event Loop continuously checks the call stack to see if there’s any function that needs to run. So it has one simple job — to monitor the Call Stack and the Callback Queue. If the Call Stack is empty, it will take the first event from the queue and will push it to the Call Stack, which effectively runs it. Such an iteration is called a tick in the Event Loop.

The above example looks normal, there’s nothing special about it: JavaScript finds things to execute, runs them in order. Let’s see how to defer a function until the stack is clear. The use case of setTimeout(() => {}), 5000) is to call a function, but execute it once every other function in the code has executed.

console.log('Hi');

setTimeout(function cb1() {

console.log('cb1');

}, 5000);

console.log('Bye');Let’s “execute” this code and see what happens:

- The state is clear. The browser console is clear, and the Call Stack is empty.

console.log('Hi')is added to the Call Stack.console.log('Hi')is executed.console.log('Hi')is removed from the Call Stack.setTimeout(function cb1() { ... })is added to the Call Stack.setTimeout(function cb1() { ... })is executed. The browser creates a timer as part of the Web APIs. It is going to handle the countdown for you.- The

setTimeout(function cb1() { ... })itself is complete and is removed from the Call Stack. console.log('Bye')is added to the Call Stack.console.log('Bye')is executed.console.log('Bye')is removed from the Call Stack.- After at least 5000 ms, the timer completes and it pushes the cb1 callback to the Callback Queue.

- The Event Loop takes cb1 from the Callback Queue and pushes it to the Call Stack(when the call stack is empty)

cb1is executed and addsconsole.log('cb1')to the Call Stack.console.log('cb1')is executed.console.log('cb1')is removed from the Call Stack.cb1is removed from the Call Stack.

Philip Robers has created an amazing online tool to visualize how JavaScript works underneath. Here we can see the phases of stack and event loop for the following JS code:

function printHello() {

console.log('Hello from baz');

}

function baz() {

setTimeout(printHello, 3000);

}

function bar() {

baz();

}

function foo() {

bar();

}

foo();It’s important to note that setTimeout(…) doesn’t automatically put your callback on the event loop queue. It sets up a timer. When the timer expires, the environment places your callback into the Callback Queue. That doesn’t mean that cb1 will be executed in 5,000 ms but rather that, in 5,000 ms, cb1 will be added to the Callback Queue. The Callback Queue, however, might have other events that have been added earlier — your callback will have to wait or call stack is not empty to push it there.

Take a look at the following code:

const bar = () => console.log('bar');

const baz = () => console.log('baz');

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo');

setTimeout(bar, 0);

baz();

};

foo();This code prints, maybe surprisingly:

foo

baz

barWhen setTimeout() is called, the Browser(Web) or Node.js start the timer. Once the timer expires, in this case immediately as we put 0 as the timeout, the callback function is put in the Message Queue.

A new concept called the Job Queue was introduced in ES6. It’s a layer on top of the Event Loop queue. You are most likely to bump into it when dealing with the asynchronous behavior of Promises (we’ll talk about them too). It’s a way to execute the result of an async function as soon as possible, rather than being put at the end of the call stack. Promises that resolve before the current function ends will be executed right after the current function.

Example:

const bar = () => console.log('bar');

const baz = () => console.log('baz');

const foo = () => {

console.log('foo');

setTimeout(bar, 0);

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

console.log('Promise starts execution');

return resolve('should be right after baz, before bar');

})

.then(resolve => console.log(resolve));

baz();

};

foo();This prints:

1. foo

2. baz

3. Promise starts execution

4. should be right after baz, before bar

5. barAnother one example:

console.log('script start');

setTimeout(function() {

console.log('setTimeout');

}, 0);

Promise.resolve().then(function() {

console.log('promise1');

}).then(function() {

console.log('promise2');

});

console.log('script end');This prints:

1. script start

2. script end

3. promise1

4. promise2

5. setTimeoutAnother one:

console.log('script start');

setTimeout(function() {

console.log('setTimeout1');

}, 0);

const foo = async() => {

console.log('foo');

return 'foo';

}

const bar = async() => {

console.log('bar');

return 'bar';

}

(async() => {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log('setTimeout2');

}, 0);

await foo();

await bar();

})();This prints:

script start

foo

bar

setTimeout1

setTimeout2const p = Promise.resolve();

(async () => {

await p; console.log('after:await');

})();

p.then(() => console.log('tick:a'))

.then(() => console.log('tick:b'));